Neither the Ukrainian famine nor the broader Soviet famine were ever officially recognized by the USSR. Inside the country the famine was never mentioned. All discussion was actively repressed; statistics were altered to hide it. The terror was so overwhelming that the silence was complete. Outside the country, however, the cover-up required different, subtler tactics. These are beautifully illustrated by the parallel stories of Walter Duranty and Gareth Jones.

Extra rewards were available to those, like Walter Duranty, who played the game particularly well. Duranty was The New York Times correspondent in Moscow from 1922 until 1936, a role that, for a time, made him relatively rich and famous. British by birth, Duranty had no ties to the ideological left, adopting rather the position of a hard-headed and skeptical “realist,” trying to listen to both sides of the story. “It may be objected that the vivisection of living animals is a sad and dreadful thing, and it is true that the lot of kulaks and others who have opposed the Soviet experiment is not a happy one,” he wrote in 1935—the kulaks being the so-called wealthy peasants whom Stalin accused of causing the famine. But “in both cases, the suffering inflicted is done with a noble purpose.”

This position made Duranty enormously useful to the regime, which went out of its way to ensure that Duranty lived well in Moscow. He had a large flat, kept a car and a mistress, had the best access of any correspondent, and twice received coveted interviews with Stalin. But the attention he won from his reporting back in the U.S. seems to have been his primary motivation. His missives from Moscow made him one of the most influential journalists of his time. In 1932, his series of articles on the successes of collectivization and the Five Year Plan won him the Pulitzer Prize. Soon afterward, Franklin Roosevelt, then the governor of New York, invited Duranty to the governor’s mansion in Albany, where the Democratic presidential candidate peppered him with queries. “I asked all the questions this time. It was fascinating,” Roosevelt told another reporter. As the famine worsened, Duranty, like his colleagues, would have been in no doubt about the regime’s desire to repress it. In 1933, the Foreign Ministry began requiring correspondents to submit a proposed itinerary before any journey into the provinces; all requests to visit Ukraine were refused. The censors also began to monitor dispatches. Some phrases were allowed: “acute food shortage,” “food stringency,” “food deficit,” “diseases due to malnutrition,” but nothing else. In late 1932, Soviet officials even visited Duranty at home, making him nervous.

In

that atmosphere, few of them were inclined to write about the famine,

although all of them knew about it. “Officially, there was no famine,”

wrote Chamberlin. But “to anyone who lived in Russia in 1933 and who

kept his eyes and ears open, the historicity of the famine is simply not

in question.” Duranty himself discussed the famine with William Strang,

a diplomat at the British embassy, in late 1932. Strang reported back

drily that the New York Times correspondent had been “waking to

the truth for some time,” although he had not “let the great American

public into the secret.” Duranty also told Strang that he reckoned “it

quite possible that as many as 10 million people may have died directly

or indirectly from lack of food,” though that number never appeared in

any of his reporting. Duranty’s reluctance to write about famine may

have been particularly acute: The story cast doubt on his previous,

positive (and prize-winning) reporting. But he was not alone. Eugene

Lyons, Moscow correspondent for United Press and at one time an

enthusiastic Marxist, wrote years later that all of the foreigners in

the city were well aware of what was happening in Ukraine as well as

Kazakhstan and the Volga region:

In

that atmosphere, few of them were inclined to write about the famine,

although all of them knew about it. “Officially, there was no famine,”

wrote Chamberlin. But “to anyone who lived in Russia in 1933 and who

kept his eyes and ears open, the historicity of the famine is simply not

in question.” Duranty himself discussed the famine with William Strang,

a diplomat at the British embassy, in late 1932. Strang reported back

drily that the New York Times correspondent had been “waking to

the truth for some time,” although he had not “let the great American

public into the secret.” Duranty also told Strang that he reckoned “it

quite possible that as many as 10 million people may have died directly

or indirectly from lack of food,” though that number never appeared in

any of his reporting. Duranty’s reluctance to write about famine may

have been particularly acute: The story cast doubt on his previous,

positive (and prize-winning) reporting. But he was not alone. Eugene

Lyons, Moscow correspondent for United Press and at one time an

enthusiastic Marxist, wrote years later that all of the foreigners in

the city were well aware of what was happening in Ukraine as well as

Kazakhstan and the Volga region:The truth is that we did not seek corroboration for the simple reason that we entertained no doubts on the subject. There are facts too large to require eyewitness confirmation. … Inside Russia the matter was not disputed. The famine was accepted as a matter of course in our casual conversation at the hotels and in our homes.Everyone knew—yet no one mentioned it. Hence the extraordinary reaction of both the Soviet establishment and the Moscow press corps to the journalistic escapade of Gareth Jones.

Jones was a young Welshman, only 27 years old at the time of his 1933 journey to Ukraine.

Possibly inspired by his mother—as a young woman she had been a governess in the home of John Hughes, the Welsh entrepreneur who founded the Ukrainian city of Donetsk—he decided to study Russian, as well as French and German, at Cambridge University. He then landed a job as a private secretary to David Lloyd George, the former British prime minister, and also began writing about European and Soviet politics as a freelancer. In early 1932, before the travel ban was imposed, he journeyed out to the Soviet countryside (accompanied by Jack Heinz II, scion of the ketchup empire) where he slept on “bug-infested floors” in rural villages and witnessed the beginnings of the famine.

In the spring of 1933, Jones returned to Moscow, this time with a visa given to him largely on the grounds that he worked for Lloyd George (it was stamped “Besplatno” or “Gratis,” as a sign of official Soviet favor). Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador to London, had been keen to impress Lloyd George and had lobbied on Jones’s behalf. Upon arrival, Jones first went around the Soviet capital and met other foreign correspondents and officials. Lyons remembered him as “an earnest and meticulous little man … the sort who carries a note-book and unashamedly records your words as you talk.” Jones met Umansky, showed him an invitation from the German Consul-General in Kharkiv, and asked to visit Ukraine. Umansky agreed. With that official stamp of approval, he set off south.

I crossed the border from Great Russia into the Ukraine. Everywhere I talked to peasants who walked past. They all had the same story.Jones slept on the floor of peasant huts. He shared his food with people and heard their stories. “They tried to take away my icons, but I said I’m a peasant, not a dog,” someone told him. “When we believed in God we were happy and lived well. When they tried to do away with God, we became hungry.” Another man told him he hadn’t eaten meat for a year.

“There is no bread. We haven’t had bread for over two months. A lot are dying.” The first village had no more potatoes left and the store of burak (“beetroot”) was running out. They all said: “The cattle are dying, nechevo kormit’ [there’s nothing to feed them with]. We used to feed the world & now we are hungry. How can we sow when we have few horses left? How will we be able to work in the fields when we are weak from want of food?”

Jones saw a woman making homespun cloth for clothing, and a village where people were eating horse meat. Eventually, he was confronted by a “militiaman” who asked to see his documents, after which plainclothes policemen insisted on accompanying him on the next train to Kharkiv and walking him to the door of the German consulate. Jones, “rejoicing at my freedom, bade him a polite farewell—an anti-climax but a welcome one.”

In Kharkhiv, Jones kept taking notes. He observed thousands of people queueing in bread lines: “They begin queuing up at 3-4 o’clock in the afternoon to get bread the next morning at 7. It is freezing: many degrees of frost.” He spent an evening at the theater—“Audience: Plenty of lipstick but no bread”—and spoke to people about the political repression and mass arrests which rolled across Ukraine at the same time as the famine. He called on Umansky’s colleague in Kharkiv, but never managed to speak to him. Quietly, he slipped out of the Soviet Union. A few days later, on March 30, he appeared in Berlin at a press conference probably arranged by Paul Scheffer, a Berliner Tageblatt journalist who had been expelled from the USSR in 1929. He declared that a major famine was unfolding across the Soviet Union and issued a statement:

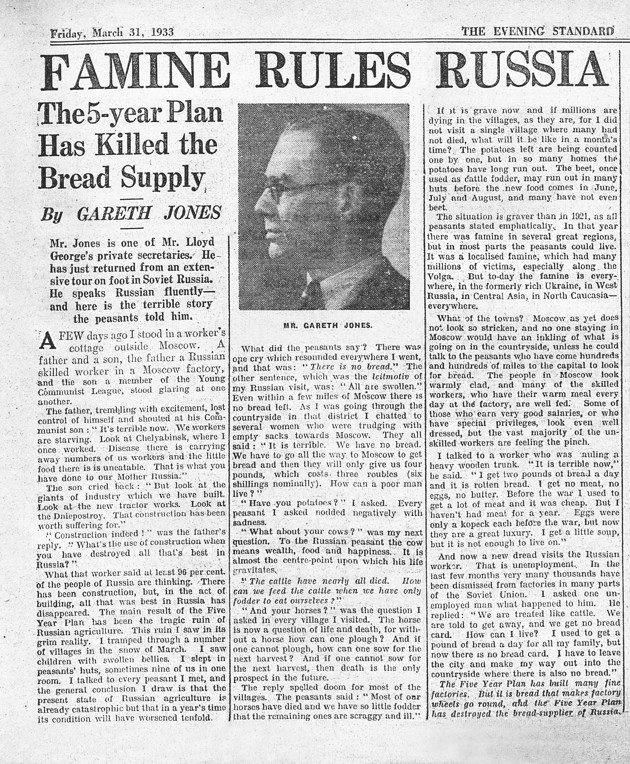

Everywhere was the cry, “There is no bread. We are dying.” This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, Central Asia …Jones’s press conference was picked up by two senior Berlin-based U.S. journalists, in The New York Evening Post (“Famine grips Russia, millions dying, idle on rise says Briton”) and in the Chicago Daily News (“Russian Famine Now as Great as Starvation of 1921, Says Secretary of Lloyd George”). Further syndications followed in a wide range of British publications. The articles explained that Jones had taken a “long walking tour through the Ukraine,” quoted his press release and added details of mass starvation. They noted, as did Jones himself, that he had broken the rules which held back other journalists: “I tramped through the black earth region,” he wrote, “because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.” Jones went on to publish a dozen further articles in the London Evening Standard and Daily Express, as well as the Cardiff Western Mail.

“We are waiting for death” was my welcome: “See, we still have our cattle fodder. Go farther south. There they have nothing. Many houses are empty of people already dead,” they cried.

It is astonishing that Gareth Johnson [sic] has impersonated the role of Khlestakov and succeeded in getting all of you to play the parts of the local governor and various characters from The Government Inspector. In fact, he is just an ordinary citizen, calls himself Lloyd George’s secretary and, apparently at the latter’s bidding, requests a visa, and you at the diplomatic mission without checking up at all, insist the [OGPU] jump into action to satisfy his request. We gave this individual all kinds of support, helped him in his work, I even agreed to meet him, and he turns out to be an imposter.In the immediate wake of Jones’s press conference, Litvinov proclaimed an even more stringent ban on journalists travelling outside of Moscow. Later, Maisky complained to Lloyd George, who, according to the Soviet ambassador’s report, distanced himself from Jones, declaring that he had not sponsored the trip and had not sent Jones as his representative. What he really believed is unknown, but Lloyd George never saw Jones again.

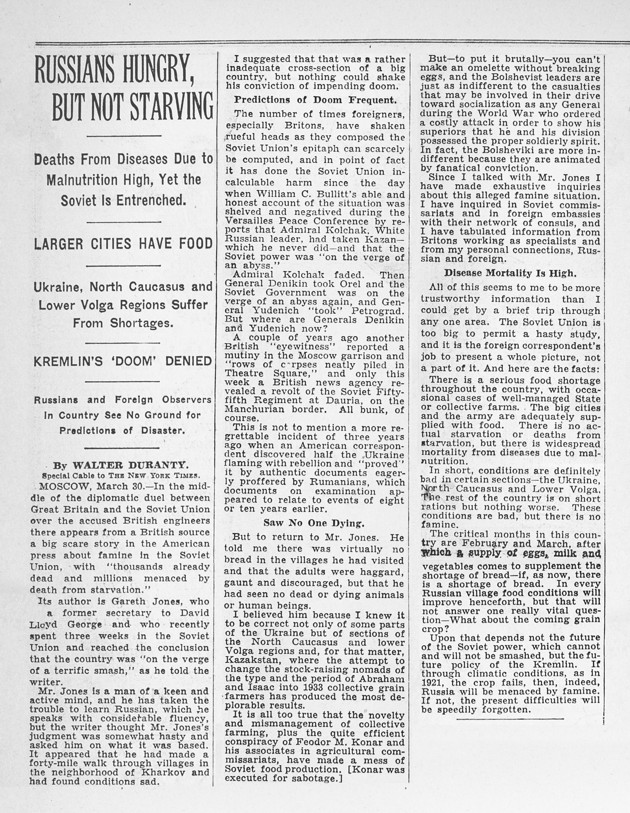

Throwing down Jones was as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes—but throw him down we did, unanimously and in almost identical formulations of equivocation. Poor Gareth Jones must have been the most surprised human being alive when the facts he so painstakingly garnered from our mouths were snowed under by our denials. … There was much bargaining in a spirit of gentlemanly give-and-take, under the effulgence of Umansky’s gilded smile, before a formal denial was worked out. We admitted enough to soothe our consciences, but in roundabout phrases that damned Jones as a liar. The filthy business having been disposed of, someone ordered vodka and zakuski.Whether or not a meeting between Umansky and the foreign correspondents ever took place, it does sum up, metaphorically, what happened next. On March 31, just a day after Jones had spoken out in Berlin, Duranty himself responded. “Russians Hungry But Not Starving,” read the New York Times headline. Duranty’s article went out of its way to mock Jones:

There appears from a British source a big scare story in the American press about famine in the Soviet Union, with “thousands already dead and millions menaced by death and starvation.” Its author is Gareth Jones, who is a former secretary to David Lloyd George and who recently spent three weeks in the Soviet Union and reached the conclusion that the country was “on the verge of a terrific smash,” as he told the writer. Mr. Jones is a man of a keen and active mind, and he has taken the trouble to learn Russian, which he speaks with considerable fluency, but the writer thought Mr. Jones's judgment was somewhat hasty and asked him on what it was based. It appeared that he had made a 40-mile walk through villages in the neighborhood of Kharkov and had found conditions sad.Duranty continued, using an expression that later became notorious: “To put it brutally—you can't make an omelette without breaking eggs.” He went on to explain that he had made “exhaustive inquiries” and concluded that “conditions are bad, but there is no famine.”

I suggested that that was a rather inadequate cross-section of a big country but nothing could shake his conviction of impending doom.

Censorship has turned them into masters of euphemism and understatement. Hence they give “famine” the polite name of “food shortage” and “starving to death” is softened down to read as “widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition...And there the matter rested. Duranty outshone Jones: He was more famous, more widely read, more credible. He was also unchallenged. Later, Lyons, Chamberlin and others expressed regret that they had not fought harder against him. But at the time, nobody came to Jones’s defense, not even Muggeridge, one of the few Moscow correspondents who had dared to express similar views. Jones himself was kidnapped and murdered by Chinese bandits during a reporting trip to Mongolia in 1935.

Loud applause followed. Duranty’s name, the New Yorker later reported, provoked “the only really prolonged pandemonium” of the evening. “Indeed, one quite got the impression that America, in a spasm of discernment, was recognizing both Russia and Walter Duranty.” With that, the cover-up seemed complete.

No comments:

Post a Comment