Matt Taibbi

On Monday, the New York Times ran a story pegged to a new poll, showing Joe Biden dragging a sub-Trumpish 33% approval rating into the midterms. The language was grave:

Widespread concerns about the economy and inflation have helped turn the national mood decidedly dark, both on Mr. Biden and the trajectory of the nation… a pervasive sense of pessimism that spans every corner of the country...

The article followed another from the weekend, “At 79, Biden Is Testing the Boundaries of Age and the Presidency.” That piece, about Biden’s age — code for “cognitive decline” — was full of doom as well:

Mr. Biden looks older than just a few years ago, a political liability that cannot be solved by traditional White House stratagems like staff shake-ups… Some aides quietly watch out for him. He often shuffles when he walks, and aides worry he will trip on a wire. He stumbles over words during public events, and they hold their breath to see if he makes it to the end without a gaffe.

Biden’s descent was obvious six years ago. Following the candidate in places like Nevada, Iowa, and New Hampshire, I listened to traveling press joke about his general lack of awareness and discuss new precautions his aides seemed to be taking to prevent him engaging audience members at events.

Biden at the time was earning negative headlines for doing things like jamming a forefinger into the sternum of a black activist named Tracye Redd in Waterloo, Iowa, one of several such incidents just on that trip.My former editor at Rolling Stone John Hendrickson, a genial, patient person whom I like a great deal, insisted from afar that Biden’s problems were due to continuing difficulties with a childhood stutter, something John had also overcome. He went on to write a piece for the Atlantic called “Joe Biden’s Stutter, and Mine” that became a viral phenomenon, abetting a common explanation for Biden’s stump behavior: he was dealing with a disability. The Times added op-eds from heroes like airline pilot Captain “Sully” Sullenberger with titles like, “Like Joe Biden, I Once Stuttered, Too. I Dare You to Mock Me.”

But I’d covered a much sharper Biden in 2008 and felt that even if the drain of overcoming a stutter had some effect, the problems were cognitive, not speech-related. He struggled to remember where he was and veered constantly into inappropriateness, challenging people physically, telling crazy-ass stories, and angering instantly. He’d move to inch-close face range of undecideds like Cedar Rapids resident Jaimee Warbasse and grab her hand (“we’re talking minutes,” she said) before saying, “If I haven’t swayed you today, then I can’t.” I called the mental health professionals who were all too happy to diagnose Donald Trump from afar for a story about the effort to remove Trump under the 25th amendment, and all declined to discuss Biden even off the record for “ethical” reasons.

This week, all that changed. Add stories like “Biden Promised to Stay Above the Fray, but Democrats Want a Fighter” and Michelle Goldberg’s “Joe Biden is Too Old to Be President Again,” and what we’ve got is a newspaper that catches real history spasmodically and often years late, but has the accuracy of an atomic clock when it comes to recording the shifting attitudes of elite opinion.

Whether through Emily Bazelon’s Times Magazine piece “The Battle Over Gender Therapy,” or Michael Powell’s “A Vanishing Word in the Abortion Debate: Women,” or even the Editorial Board argument from late May, “The War in Ukraine is Getting Complicated, and America Isn’t Ready,” the Times has become a place where the public often learns about key facts, pressing international controversies, or trends in American thought only once these have been deemed suitable for public consumption by an unseen higher audience. An all time effort in this direction was “Hunter Biden Paid Tax Bill, but Broad Federal Investigation Continues,” in which the paper allowed some of its better reporters to quietly confirm a story about Hunter Biden’s laptop two years after keeping more or less mum as the story was tabbed Russian disinformation.

Along with companion outlets like the Washington Post and The Atlantic (as pure a reflection of establishment thought as exists in America), the paper in this sense fulfills the same function that Izvestia once served in the Soviet Union, telling us little or even less than nothing about breaking news events (“Can NATO Long Exist?” was among Pravda’s final questions in 1991) but giving us comprehensive, if often coded, portraits of the thinking of the leadership class.

The May Ukraine editorial in the Times in this respect was fascinating. From the first days of the invasion, the Times followed every other paper in cartoonizing the conflict as a standard Hitlers-versus-baby-seals showdown (“Zelensky’s Heroic Resistance is an Example to the World”), pledging to brook no talk of anything but fighting to the end, “even if the pain it will cause is still unknown.”

Months later, the paper began hinting that intelligence officials like Avril Haines believed the war could take “a more unpredictable and potentially escalatory trajectory,” with possible “extraordinary costs and serious dangers.” The paper went on to make arguments that had led to accusations of treason and Putinism when they came from outside sources before:

In March, this board argued that the message from the United States and its allies to Ukrainians and Russians alike must be: No matter how long it takes, Ukraine will be free… That goal cannot shift, but in the end, it is still not in America’s best interest to plunge into an all-out war with Russia, even if a negotiated peace may require Ukraine to make some hard decisions.

Reporting on Ukraine from the start was reduced to a demented satire, projecting the disordered thinking of defense lobbyists in suburban Maryland and Virginia, to whom Ukraine couldn’t be just a victimized basket case of an ex-Soviet state with a nearly identical set of regressive cultural bugaboos as its northern neighbor, but a thriving paradise of progressive democratic values, a sort of Slavic Haverford, under siege by the Russian Reich.

The contortions have been breathtaking. When evil always-villain Tucker Carlson described Ukraine as “not a democracy,” Washington Post fact-checker extraordinaire Glenn Kessler seethed but had to hold his Pinocchios, conceding that even Freedom House could only describe Ukraine as a “transitional or hybrid regime.” But, Kessler snapped, Ukraine was only slightly less of a democracy than, say, the regime of Viktor Orban:

Hungary, Carlson’s fave, is also listed as a “transitional or hybrid regime” and does not rank much higher than Ukraine. Ukraine’s overall Freedom House score, moreover, is higher than that of Mexico and Indonesia, two countries often labeled democracies.

All this takes place while Internet censorship campaign over Ukraine has massively accelerated. Quietly, as if pulled across a finish line by mice, a campaign to erase or marginalize virtually every non-elite voice critical of American foreign policy has been all but completed. From Oliver Stone (whose U.S.-critical movie Ukraine on Fire was suspended then flagged on YouTube) to Consortium News to Mint Press to former UN weapons inspector Scott Ritter to Chilean YouTube personality Gonzalo Lira (who currently lives in Kharkiv and has had multiple on-the-ground reports removed) to a slew of other voices, virtually everyone on the naughty list has either been demonetized, denied services by payment processors like Venmo or PayPal, or banned from platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Noam Chomsky made a few waves in CounterPunch a few weeks ago when he said “censorship in the United States has reached such a level beyond anything in my lifetime,” adding that things had reached “such a level that you are not permitted to read the Russian position. Literally.” He went on:

Americans are not allowed to know what the Russians are saying. Except, selected things. So, if Putin makes a speech to Russians with all kinds of outlandish claims about Peter the Great and so on, then, you see it on the front pages. If the Russians make an offer for a negotiation, you can’t find it. That’s suppressed. You’re not allowed to know what they are saying. I have never seen a level of censorship like this.

If your response is, So what?, journalism probably isn’t the profession for you. Unless we’ve moved off the belief in this business that it’s better to know more than less, blacking out huge factual territories on purpose is an insane strategy, automatically a disservice to general audiences and political decision-makers alike.

I reached out to Chomsky this weekend and asked him what in particular it is about the Ukraine conflict that’s brought out such an aggressive response.

“Putting aside the dangers, which are all too real,” he says, the unusually intense response is “part of something much worse: the general atmosphere of irrationality engendered by the whole Ukraine affair. It ranges from the nutcases like Fukuyama assuring us that there’s no threat of nuclear war if we escalate (and the official policy that is not much different), to the ‘left’ shouting slogans about how we have to defend Ukraine and punish Russia no matter what, and any voice that breaks unanimity has to be stilled, maybe crushed.”

Unlike previous “content moderation” controversies involving everything from Russian disinformation to Covid-19 policy to Canadian Trucker Protests, there’s been very little partisan blowback to Ukraine-based deletions or even confiscations by firms like PayPal, which makes the significance of this campaign obvious: Ukraine is destined to legitimize Internet censorship for Middle America.

Roughly two years ago I spoke on background with one of the CEOs of a major Internet platform, who walked me through his company’s somewhat tortured but at least still logical thought process on moderation. Their idea was to only intervene in situations involving clear election misinformation (for instance, an ad targeting black voters which displayed an incorrect address of a voting location), a genuine health threat (e.g. posts that gave potentially health-imperiling advice), or incitement to violence.

Ukraine is a step beyond. This censorship doesn’t claim to be about saving lives, preventing “threats to democracy,” or even, really, about “misinformation.” As has been made clear in a variety of episodes, including the one involving Ukraine on Fire, even true information that runs counter to prevailing narratives is regularly excised.

The case of Ukraine on Fire is particularly interesting. Both YouTube and Vimeo initiated removal actions shortly after the invasion, as if the 2016 film suddenly acquired offensive traits in early 2020, only to pull back amid pubic pressure.

“After the [invasion], our film gained a wide popularity and was on top of the charts on Apple TV and Amazon,” says producer Igor Lopatonok. “Suddenly, YouTube deleted Ukraine on Fire… VIMEO was also following steps of YouTube and canceled not only that title, but our entire channel. After the press started mentioning this, YouTube backed off and restored our film feed, but restricted visibility.”

Neither of the platforms suggested factual inaccuracy of Ukraine on Fire, variously going after it for “graphic content” or saying it needed to be age-restricted. The real problem was that it depicted inconvenient facts, like for instance that Western-friendly former president Viktor Yuschenko, best known in America for being the seeming victim of a gruesome dioxin poisoning attempt, once awarded a posthumous “Hero of Ukraine” award to notorious Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera, said to have joined the Einsatzgruppen in a series of pogroms in Lviv in June of 1941.

One can disagree with the film, but the rationale for removing or age-restricting it is incredibly weak. “Overall, that situation with attempted censorship just fueled demand,” says Lopatonok.

Ukraine war reporting in papers like the Times and the Post has prioritized being faithful to first-blush government explanations, like the March 11 Times “Fact Check” reading, “Theory About U.S.-Funded Bioweapons Labs in Ukraine Is Unfounded.” Less than two weeks after, the State Department conceded that “the U.S. Department of Defense’s Biological Threat Reduction Program (BTRP) works with the Ukrainian Government to consolidate and secure pathogens and toxins of security concern in Ukrainian government facilities.”

By then, it was too late for voices who’d talked about this before it was permissible. On April 13, 2022, the “Tech Transparency Project” (TTP), an online site funded by groups like the Omidyar Network and dedicated to “pressing for accountability” from platforms like Facebook and Google, ran a piece called “Amazon-Owned Twitch Spreading Russian Misinformation on Ukraine.” The article accused a number of independent media figures, including a Los Angeles-based online broadcaster named Jackson Hinkle, of “actively fueling Russian propaganda,” which included claims “conspiracy theories that the U.S. is running biolabs in Ukraine.”

The Project accused Hinkle of having “offered several streams with the title ‘PUTIN 71% APPROVAL’” (everyone from Reuters to the Wall Street Journal reported the same poll results), and of suggesting Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky had fled his country, albeit in a joking way:

How quickly does Internet censorship work now? That same day, a Financial Times reporter called Twitch to present the firm with the “findings” of the TTP. It look less than a few hours for the company to act. An account called “Infrared,” the FT gloated, was “banned shortly after the company was contacted by the Financial Times on Wednesday evening,” as were “three others cited in the TTP report,” including Hinkle.

“The story from the Financial Times came out within a matter of minutes of us getting banned,” Hinkle said.

Hinkle went on to be cut off from payment services by Venmo and PayPal (which seized about $100 in his account in the process). Just this past week, he was permanently demonetized by YouTube, eliminating 80% of his income. In fact, just as this article went to press, Hinkle received a second “community guidelines” strike. Because he believes this means “YouTube is combing through my old videos and taking them down one by one,” Hinkle says, “I’m at the point now where I’m probably going to take down all of my old videos to avoid a third strike.” I reached out to YouTube, which initially seemed keen to provide an answer, but they’ve so far not provided an explanation as to what constitutes Hinkle’s “harmful” conduct.

Between the actions of Twitch, PayPal, Venmo, and YouTube, that’s an awful lot of institutional effort to quiet one Jackson Hinkle, who doesn’t belong to any of the traditional phyla of censored Internet figure. He’s not an anti-vaxxer, nor an election denialist, nor any kind of white nationalist. His show is focused on Ukraine. “My videos before the war started were getting maybe not even 10,000 views,” he says, adding that he was averaging “like 30,000-100,000 views” when hit with YouTube’s decision.

“The belief that we should all be pro-censorship about the Internet is a commonplace thing now,” says Hinkle. “And it scares the shit out of me.”

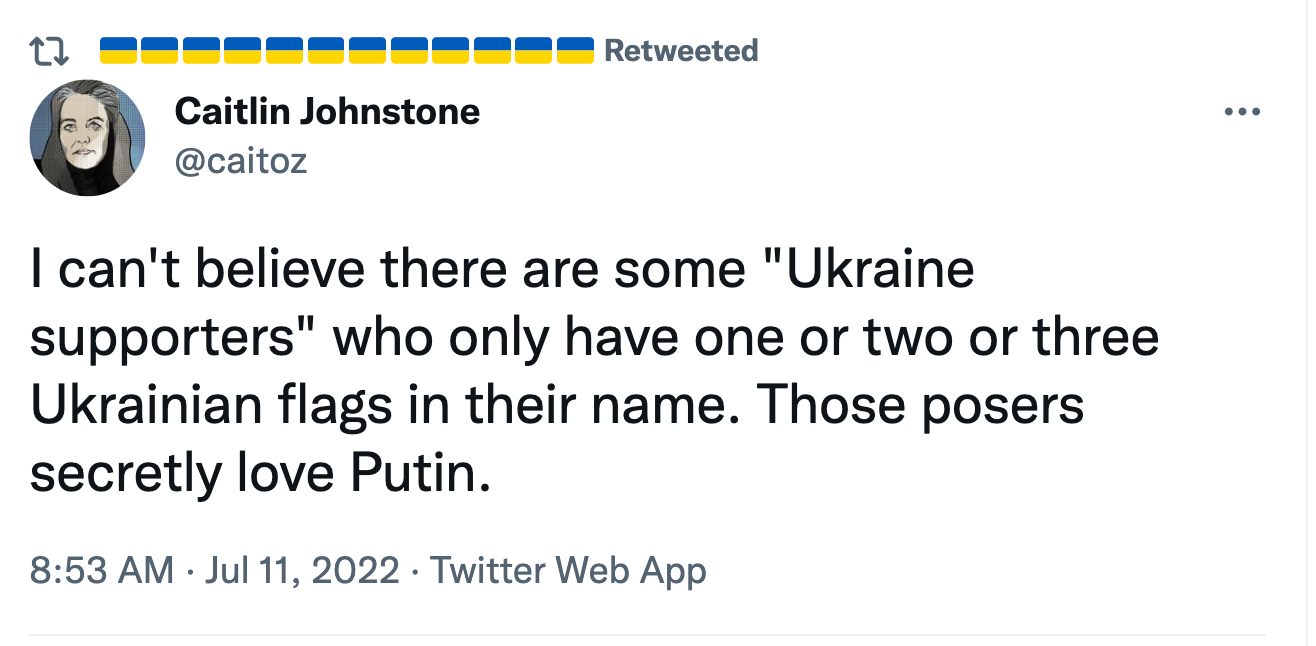

Ukraine as a media phenomenon has become the modern version of the Great Loyalty Oath Crusade, where failure to salute often enough and with enough enthusiasm can betray secret unorthodoxy. Writers like Caitlin Johnstone are lampooning the endless worship of this latest Current Thing by plastering her tweets with the maximum quantity of Ukrainian flags, and faux-castigating everyone with fewer:

This back-and-forth has inspired some people to veer into territory that offends even some usually ardent speech supporters (I heard more than one person Monday griping about Hinkle headlines like “Putin owns the libs”). However, the reason for banning or demonetizing such people is now purely political, no longer bothering with the fig leaf of “lives at stake.”

We’ve reached the speech el Dorado of intel nerds, the search for which began with the exile of people like Ed Snowden and continued with the prosecution and extradition of Julian Assange: media companies and Internet platforms are agreeing to bluntly disallow criticism or mockery of American foreign policy on those grounds alone.

A major preoccupation of the censorship/propaganda effort has been squelching talk about the background to the invasion. Even if you believe, as I do, that Putin’s invasion was totally unjustified, we know from countless sources that United States officials worried that trying to expand NATO to Ukraine might lead to an armed response.

Former Ambassador and CIA Director William Burns outlined it in his famous 2009 “nyet means nyet” memo, released by Wikileaks, quoting a Russian official saying that “integration into NATO would seriously complicate the many-sided Russian-Ukrainian relations,” and Russia would “have to take appropriate measures.” George Kennan, the once respected author of American containment policy, said “expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.” Former Defense Secretary William Perry concurred, and onetime Ambassador to Russia Jack Matlock expressed similar sentiments.

But people like former ambassador Michael McFaul, with whom I have the misfortune to be personally familiar — a human haircut to whom the English language is a major challenge and the Cyrillic alphabet is the moon — have been plastered on television, pushing the idea that Russia never cared about NATO. McFaul wants to pretend that from Kennan to Perry to Burns to Matlock, neither his predecessors nor his successors heard Russian officials freaking out about NATO. He’s been insisting that Putin meant it when he said, “We of course are not in a position to tell people what to do,” and “Complaints about NATO expansion never arose” at, for instance, the 2010 NATO summit in Lisbon.

These facts don’t justify Putin’s invasion, but do show Americans understood it was a possible response to years of policy decisions, and they’re being whitewashed in furious fashion. Much in the same way “no evidence of criminal wrongdoing” became a required Surgeon General’s warning in coverage of the Hunter Biden laptop story, “unprovoked invasion” has become a near-mandatory descriptor. Chomsky believes this is central to why the clampdown is so intense.

“It’s become a rigid rule to use that phrase,” Chomsky says. “The only explanation is that it’s understood, at some level, that it was of course a provoked invasion, and we have to beat down that understanding by all means possible.” Similarly, he says, “the case for fighting a proxy war to ‘weaken Russia’ is unsustainable on rational grounds, so the only recourse is irrationality.”

I’m not sure I’d go as far as to call it a “provoked invasion,” but I might use the term “expected,” and suggest an elite re-think of certain decisions is coming. In the same way the Times is finally getting around to telling us Washington is worried about Joe Biden’s age, proposals for various Ukraine exit strategies and diplomatic solutions will likely start creeping onto front pages soon.

The Ukraine war began with great trumpet-calls, as there seemed to be hope among the political class that it would reorient the public away from its unhelpful populism-vs-elites fixation and back in the direction of “democracy versus autocracy,” rehabilitating military expansionism in the process.

It hasn’t worked out, in part because the war hasn’t gone as hoped, and the expected political upheaval against Putin hasn’t materialized. Apart from the sale of a ton of weapons, the only thing the war has for sure accomplished for Washington politically is making censorship more broadly acceptable. Compared to the real horrors people in the region are experiencing, that may not sound like much, but it’s no small thing, and be wary of getting too used to this Izvestia-style system as normal. It isn’t. It’s nuts, and always will be.

No comments:

Post a Comment