America’s institutions need structural reform. We need it in academia, we need it in the corporate world, and we need it in government. In all of these fields, the structures, incentives, and institutions that have grown up over time have been destructive, and need to be fundamentally transformed.

I’ll be writing about all of these things down the line, but for now let’s start with government. Though you don’t hear a lot about it on the right, the left is all bent out of shape over the prospect that a Republican administration elected in 2024 might partially deconstruct the existing protected civil service. I, on the other hand, am excited about that prospect, and only wish they’d go farther.

Prior to the adoption of the Pendleton Act in 1883, government employment operated according to the “spoils system,” which meant that hiring in the executive branch was controlled by the Executive. When a new administration came in, everyone’s job was up for grabs, at least potentially. This “rotation in office” had several advantages, which were widely appreciated at the time, and propounded by presidents from Jefferson to Jackson to Lincoln.

“Jackson argued that one serving in government for too long would inevitably lose sight of the public interest and come to use office for personal gain. He also maintained that government was or could be made simple enough for men of ordinary ability and experience, so ‘more is lost by the long continuance of men in office than is generally to be gained by their experience.’”[i]

Contrary to popular belief, though, the arrival of a new president didn’t mean that everyone left. Even Andrew Jackson, upon taking office, replaced only about 10% of the federal work force with his own people. Every president understood the value of continuity, and hiring new people is hard work.

But under the spoils system, the fact that the president could replace anyone mean that everyone worked for him. And that meant both that everyone was responsible to the president, and that the president was responsible for everyone in the government, and everything the government did. This is consistent with the Constitution’s vesting clause, which provides that “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” If the executive branch does it, it’s an executive power, and if it’s an executive power it should be controlled by the president.

Contrast this to a “professional” civil service, in which the president does neither the hiring nor the firing, except with regard to a comparatively small number of senior officials. The civil service doesn’t think of itself as working for the president, really, and will happily drag its feet when it doesn’t like the president’s priorities. And when the bureaucracy misbehaves, or fails to perform, the president can, at least to a degree, blame its recalcitrance for the trouble or lack of results that occurs.

Congress is also let off the hook, yet simultaneously weirdly empowered. Congress can blame “the bureaucracy” for bad things, even when those things result from laws that Congress has passed. Then it can turn around and “help” constituents by intervening with the bureaucracy it has rendered dysfunctional, earning gratitude that may be deserved in a narrow sense, but not in terms of the big picture.

Under a spoils system, on the other hand, nobody gets off the hook. If the bureaucracy misbehaves, the president can fire the misbehavers. If Congress is unhappy with what bureaucrats do, they can demand that the president fire them, and make an election issue out of it if they want.

So why did we wind up with a civil service? As is typical, the fantasy of a neutral, efficient, expert civil service was laid next to the reality of a messy functioning government. But, as is also typical, the fantasy in practice turned out to be considerably less appealing than as proposed.

The big objection to abolishing the protected civil service is that government by “expertise-driven civil service”would be gone. The response to this objection is twofold. First, we don’t have an “expertise driven civil service.” At least the record of our civil service in addressing problems has been pretty unimpressive, and not particularly marked by expertise. From government nutrition guidelines, which were based on politics and bad science, to the Covid fiasco, to energy policies and education, it’s hard to think of very many significant areas where neutral, technocratic expertise has carried the day. Looking on this record, I’ve commented in the past on the “suicide of expertise,” and I think it’s pretty obvious now that the expertise has often been a sham. (Or, even when it existed, has been subordinated to politics: Released emails, etc., have revealed that Anthony Fauci et al. knew that what they were telling the public wasn’t true, and in fact were saying the opposite in private, but lied to the public anyway.)

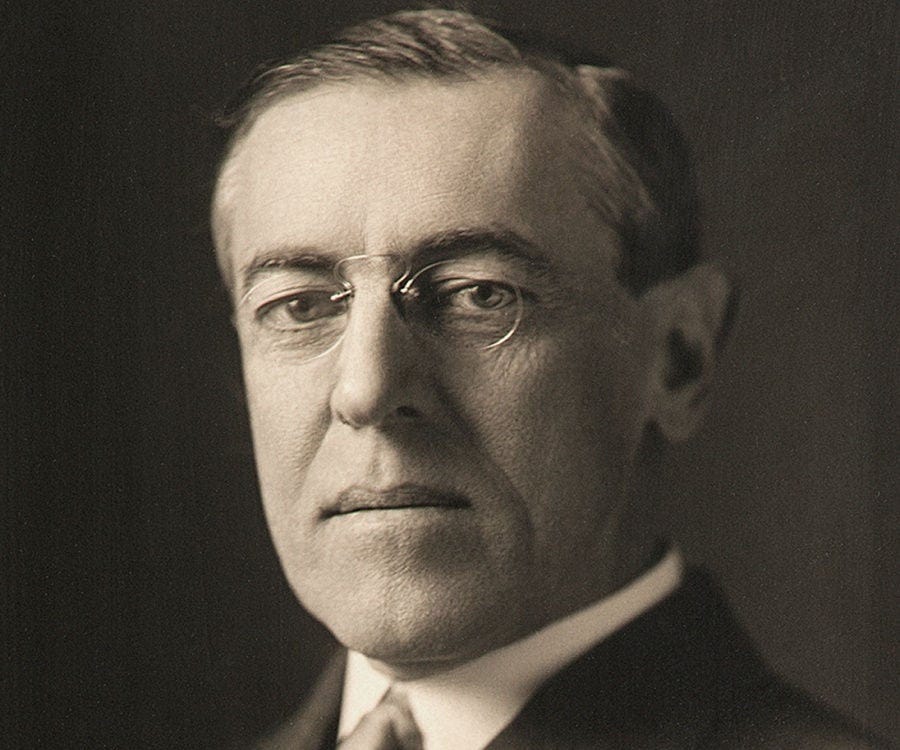

The modern civil service system (post-Pendleton Act) – like so many calamities of the 20th Century – sprang from the brain of Woodrow Wilson, a political scientist before he was president, who wrote of the importance of separating politics from administration. In his view, cool, technocratic administrators would execute the policies chosen by politics – though with the suggestion that politics should generally defer to their expertise. That theory may have seemed beguiling in the late 19th Century, but by the 21st Century it has become clear that that’s not how any of this works.

All of this would be true even if the civil service was nonpartisan, or at least divided along partisan lines that resembled those of the nation at large. This is, of course, not the case at all. The civil service is effectively a left-liberal a monoculture, with its primary loyalty being to the Democratic Party. (And donations from federal employees heavily favor Democrats). The politicized behavior of the Department of Justice, FBI, IRS, and other federal agencies during the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations has made that obvious.

So the question isn’t whether we’re going to have a nonpartisan, expert civil service or a partisan nonexpert one. The question is whether we’re going to have a calcified, one-sided partisan nonexpert service or a partisan nonexpert service that changes its composition and is subject to democratic supervision. As I’ve argued elsewhere, political turnover helps limit special-interest domination in politics. But the lack of political turnover in the bureaucracy means that there’s no such effect in the part of the government that does most of the work.

Replacing the civil service, which I think has indisputably failed to fulfill the promises of its champions, with something more politically responsive is likely to be better, and certainly more in line with notions of democracy, than leaving most of government to an unaccountable left-liberal gentry class monoculture.

And that raises another point. The takeover of the civil service by “professional” bureaucrats who get there in part by taking exams is just another example of the colonization of formerly diverse professions by the gentry class. (Journalism, formerly a blue collar profession and now dominated by college grads, frequently from places like Columbia, is another).

Writing in 1937, William Turn defended patronage against the claims of expertise and the “hysterical indictments of political patronage which are made today with little or no actual knowledge of what it is about.” His argument was that turning the civil service over to the gentry class removed a major incentive for ordinary Americans to participate in politics. Under patronage, distinguishing yourself in party work could earn you a pleasant job. And it was disciplined, because bad patronage appointments weaken the party.

Without patronage the only reason to volunteer was for ideological reasons. And keeping ordinary Americans involved in politics was important for “keeping in close touch with the great masses of ‘average folks’ whose participation is vital to any truly democratic process, learning what they are thinking, and interpreting for them the policies which are being put into effect.”[ii]

Even in 1937, Turn was decrying the “chasm” that had opened up between the governing class and society at large,[iii] and that chasm has grown much wider in the near-century since. And Turn was already warning against the gentry-class takeover I mention above: “Quite aside from the unsatisfactory character of the type of person attracted by the civil service procedure, there is good reason to question the accuracy of an arbitrary examination (or the possession of a college degree) as a true measure of an applicant’s ability.[iv]

And in prescient terms, Turn notes: “Patronage appointments for demonstrated party loyalty seem to me most likely to promote efficiency. Too light weight is given to the protection which patronage gives the government against bureaucratic sabotage, which its enemies naively deny.”[v] No president can be effective if every policy must be filtered through a hostile bureaucracy. One suspects that is the goal, at least where Republican presidents are concerned.

Well, this essay has gone on long enough. But as people on the left claim that an elimination (or, in actuality, reduction) of protected bureaucracy will somehow lead to “autocracy,” it’s worth noting that the nation existed for a century without it. And the notion that making the federal government as a whole more responsive to the will of the people as expressed through elections is somehow “autocratic” is itself self-refuting among anyone capable of thought.

Pretty much everyone agrees that the government we have now isn’t working. Shouldn’t we consider a change? The hysterical response to any proposal to depart from the status quo is meant to prevent that consideration.

No comments:

Post a Comment